Aaron Swartz stood up for freedom and fairness – and was hounded to his death

7 February 2015

The internet

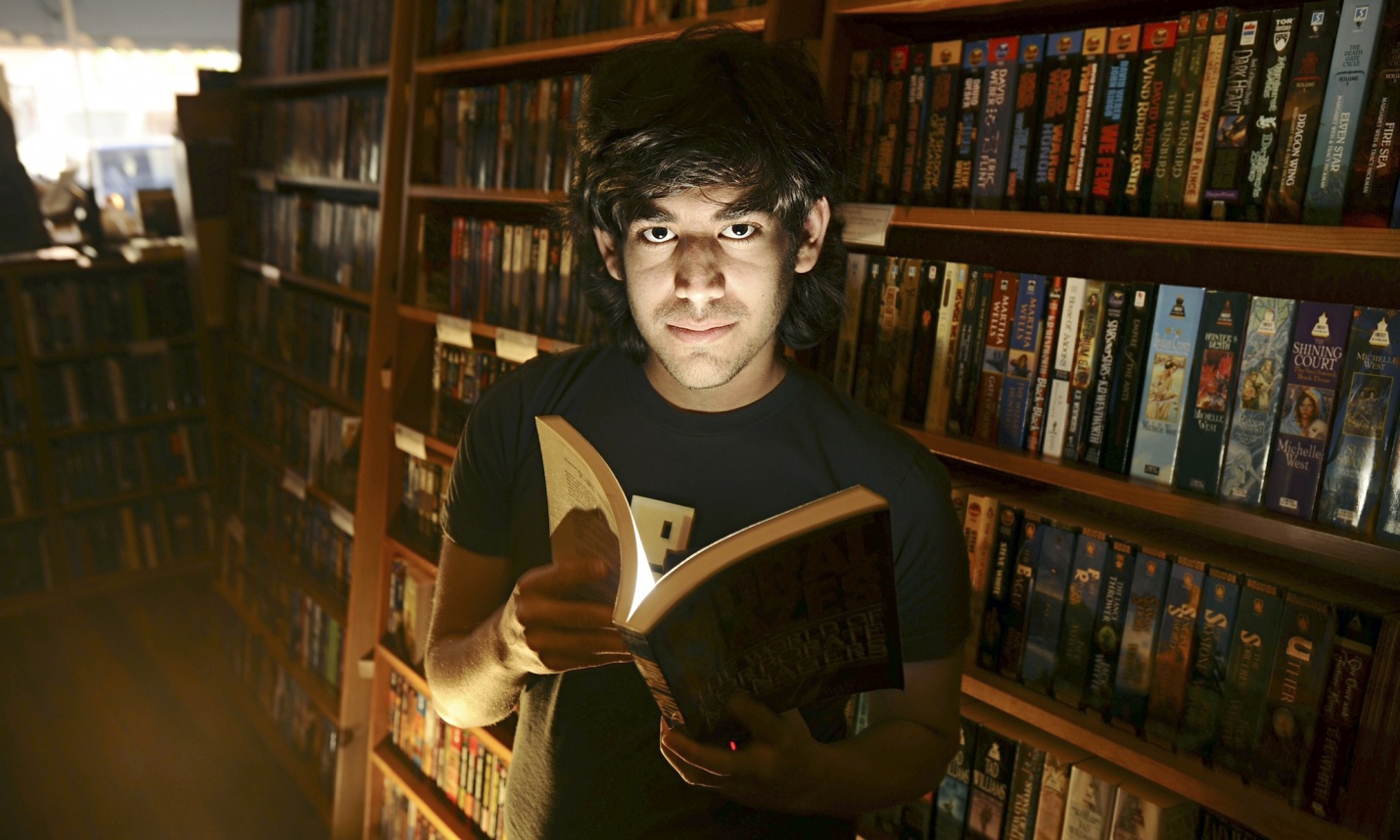

activist who paid the ultimate price for his combination of genius and

conscience

Photograph: Noah Berger/Reuters

On Monday, BBC Four screened a remarkable film in its Storyville series. The Internet’s Own Boy told the story of the life and tragic death of Aaron Swartz, the leading geek wunderkind of his generation who was hounded to suicide at the age of 26 by a vindictive US administration. The film is still available on BBC iPlayer, and if you do nothing else this weekend make time to watch it, because it’s the most revealing source of insights about how the state approaches the internet since Edward Snowden first broke cover.

3 / 5 stars

A well-constructed telling of the

life, prosecution and death of US hacktivist Aaron Swartz,

writes Mark Kermode

To say Swartz was a prodigy is an understatement. As an unknown teenager he was a co-designer of tools – like RSS and Markdown and of services like Reddit – that shaped the evolution of the web. He was also the kid who wrote most of the code underpinning Creative Commons, an inspired system that uses copyright law to give ordinary people control over how their digital creations can be used by others.

But Swartz was far more than an immensely-gifted programmer. The Storyville film includes home movies which show the entrancing, voraciously-inquisitive toddler who was father to the man. As he grew, he displayed the same open, questioning attitude to life one sees in other geniuses who are always asking “why?” and “why not?” and driving normal people nuts.

I never met Aaron (though we had a mutual friend) but I spotted him early when he first surfaced as a blogger. What struck me instantly was the freshness and originality of his authorial voice. He was very young when he went to Stanford, and he wrote about the attitudes and social mores of his classmates, many of them brats of the American elite, with a raw freshness and naivete that was startling. He didn’t belong there; he felt himself an outsider; but at the same time he wasn’t judgmental, and ithat combination of candour and uncertainty was attractive and unusual.

As he grew, one could see him becoming more and more interested in politics. And this too was predictable, for nobody with that razor-sharp intelligence could look at neoliberal capitalism and not see the unfairness, hypocrisy and inequality that lies beneath it. So he morphed into the most technologically-gifted political activist in history. He looked for instances of manifest unfairness and developed software to remedy it. Discovering that the provision of court transcripts in the US was essentially a commercial racket, he teamed up with other activists to right an obvious wrong: that the law was only readable by those with money.

He was similarly exercised at the fruits of taypayer-funded scientific research being monetised by a few ruthless publishing firms which charge outrageous fees to access the resulting academic papers. His first foray into this field involved downloading a trove of medical research papers and then data-mining them to uncover hitherto-undetected links between pharmaceutical firms and the authors of articles in prestigious journals.

His downfall came when he turned his attention to JSTOR, a digital library of academic articles hidden behind a paywall. He devised a method of downloading large numbers of articles from JSTOR, using a computer hidden in a closet at MIT. He was arrested in January 2011 and pursued by federal prosecutors with a vindictive zeal, eventually being indicted on a raft of charges which carried a potential jail sentence of 35 years. Ground down by this, he hanged himself on 11 January 2013. News of his death left countless people saddened and enraged. What had made the Feds so vindictive? Sure, he had broken the law. But it wasn’t as if he’d hacked a bank. What came to mind was Alexander Pope’s rhetorical question: Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?. “The act was harmless” wrote Tim Wu, a law professor at Columbia. “There was no actual physical harm, nor actual economic harm. The leak was found and plugged; JSTOR suffered no actual economic loss. It did not press charges. Like a pie in the face, Swartz’s act was annoying to its victim but of no lasting consequence.”

One explanation for the vindictive prosecution puts it down to a politically ambitious federal attorney anxious to make a name for himself. But there is a darker, interpretation – that the authorities had noted how effective Swartz had become as an activist (he had, after all, mobilised the net community to stop the internet censorship legislation of the SOPA bill), and they were determined to make an example of him pour décourager les autres. Which, if true, would mean the Obama administration has taken a leaf out of the Chinese book on internet control: people can say more or less what they like online; but the moment they look like mobilising people, then you come down on them like the ton of bricks that crushed Aaron Swartz.

http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/feb/07/aaron-swartz-suicide-internets-own-boy